Watching the Hours Float By in McCloskey’s Time of Wonder

In the pale blue light of early evening, two children silently glide across a luminous sea in a slim rowboat, washed with crisp swaths of pale moonlight across bench seats. The older child with auburn hair reflecting the sky gently rows the boat. She gazes with downcast eyes past the long slender oar to a single series of concentric ripples—smooth rings of opaque paint hovering above the billowing, seeping watercolor, orbiting a central point of contact heavy not with mass but with crystallized motion frozen in time. The younger child, short blond hair drawn back at the nape, peers over the boat’s hull to investigate the water as well, the beam of her flashlight shifting from chalky white to watery green as it plunges into the depths. A crab nestled in murky watercolor sits stunned with stage fright under the circle of light, his position at the extreme corner of the page threatening a skittish flight, yet he remains static as if enveloped not in warm summer brine but in museum glass. Both girls search, probing nature for its endless treasures but finding instead something less tangible—a fleeting moment of childhood summer immortalized in paint and gauche.

In Robert McCloskey’s Caldecott-winning 1957 picture book Time of Wonder, summer has arrived for a family vacationing on an island off the coast of Maine, and as is wont to happen in the languid days of July and August, time behaves strangely, shimmering and warping like heat radiating from sun-baked stones. For adults preoccupied with worldly concerns, summer passes swiftly and surreptitiously, but for children especially those who know where to look, summer lasts forever. McCloskey’s stunning watercolor illustrations invite the reader to join the two young characters in their contemplative observation of sunsets and sea life, resulting in a symbiotic relationship in which both reader and picture pass life-giving nutrients between the permeable page. It may seem odd to suggest that the picture, an inert object, may want something from its viewer, but W.J.T. Mitchell argues that all pictures, no matter how seemingly self-reliant in their quiet beauty, have a fundamental deficit—a lack of power woven into that paper on which they are printed—a lack that fuels desire. Pictures are depictions of things, incomplete symbols that only gain true potency when a viewer beholds them. McCloskey’s pictures yearn for what they lack—they ache for time—for a living, breathing, experience of time that ebbs and flows. The pictures, text, narrative, even the pages themselves hang ripe with symbols of time that cannot tick until the reader opens the cover. McCloskey’s Time of Wonder is ready to make a trade—a boat ride into the awe of nature in exchange for your time.

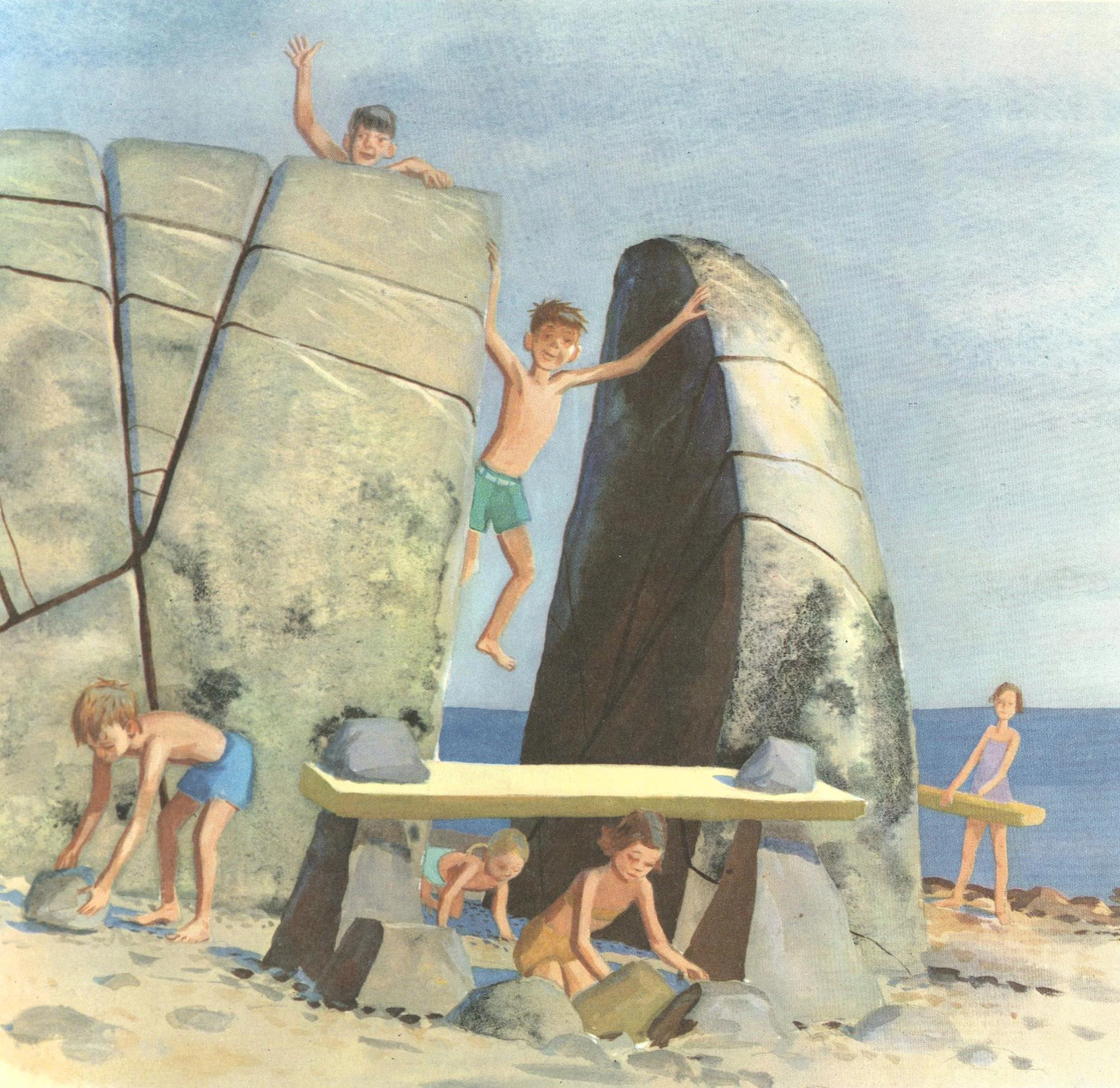

Reading A Time of Wonder aloud becomes the first act in this transactional relationship. At 63 pages, it is nearly twice the length of the standard 32-page picture book. While never dull, the weight of the time invested is palpable by the halfway point. Like a long languid summer, the plot stretches out filling the space with simple poetic pleasures and pictures—a forest shrouded in marine fog, a blanket of stars reflected in a glassy sea, a bright full moon radiating rings through dispersing clouds. The pictures, like a genial grandmother longing for a front porch visit, want you to sit with them and stay a while, enjoying the shifting kaleidoscope of watercolor washed skies in an almost meditative experience. The narrative lolls blissfully—the two girls appear for the first time as they giddily scramble over seaside rocks and amble through fern-filled forests and sun-splashed beaches, engaging in the kind of invaluable unstructured play in nature that has all but vanished from the lives of modern children. Nothing really happens in the first half of the book, and in that fertile quiet space, time multiplies. By the arrival of the hurricane, the reader has spent almost an entire summer on the island, and to a mind steeped in the slow moving currents of island life, the storm becomes an epic drama. The howling wind bursts onto the pages, filling the page with tattered ribbons of white, black, and taupe and frantic splatters of steely blue, a frothy amalgam of sea and sky that threatens to obscure even the type that on other more serene spreads is tucked safely in white housing. The painterly maelstrom screeches into the living room—scattered books hang in mid air, a tablecloth billows in frozen ripples, a lamp tilts as if resisting gravity—a split second in infinite suspension. With its contemplative attention focused on the small beautiful moments of life, the book has stopped time, a version of what Jenny Odell in her book How To Do Nothing calls a “re-rendering of reality” achieved by a shifting of our attention from the distractions of the world to the present moment. The pictures know that they offer only a secondary, skewed experience of this phenomenon—a window into nature mediated by paper and paint—and they compel the reader to go outdoors and revel in the beautiful nothings of the world where time slows but, unlike in books, never completely stops.

Far from serving as just a vehicle for content, the paint itself in McCloskey’s pictures also reveals a yearning for time, artifacts of hours that have long since lapsed. Unlike acrylic and gauche that coat the surface opaquely, watercolor descends like a diaphanous veil, rendered more transparent with the addition of water or more muddled as colors mix. Its application on wet paper send pools of pigment into seeping blooms, growing infinitesimally until the paper dries and locks in this elapsed time. In the rowboat where the girls search for undersea crabs, the crystallized blooms of time are particularly palpable, bleeding into webbed veining structures of black and red like plumes of ink from a frightened squid that has long since absconded. Painter David Hockney writes that a painting contains the amount of time that the artist spent creating it, contributing to his preference for the snail pace of oil paints and his initial disavowal of photography, which in its pure form captured only a split second of time. McCloskey’s individual watercolor illustrations took far less time to create than an oil painting, but multiplied by the thirty images contained in his book, the time encased in these pages is significant. While watercolor is ephemeral, retaining the possibility to be reworked even after drying, book reproductions encase this time under glazes of glossy paper. The only way for a picture to compensate for this loss is to transfix the viewer, siphoning time from their gaze. Pictures dream of trading places, of becoming the beholder and not just the beheld, of gazing out at the reader—an object in the natural world more real than the painted crabs and ferns they gaze at on their static, timeless pages.

The theme of impermanence hangs low and thick in Time of Wonder, like the marine layer that envelops the bay each morning and flits away by lunch. With wide landscape shots full of dramatic skies where boats bob like miniature toys, McCloskey positions the weather and all its rapid, radiant permutations as the protagonist of this tale. Each page turn reveals atmospheric shifts, the sky quickly moving from thin washes of gray fog, to hazy butter yellow sunshine, and finally to foreboding streaks of gray clouds bleeding into the sea—a dazzling visual simulation of the relentless passing of time. Water, with its unsteady surface and rolling tides, also carries the weight of time frozen in its glassy depths. In a particularly jovial scene, a gaggle of children populate a shelf of sandy rock bisected by deep glacial scars—lines shaky and irregular as if struggling under the immensity of depicting millions of years of geological tumult. Children dive from the edge, suspended mid-leap in candy-colored bathing suits over a mirror-like ocean—a jump that would be perilous if performed one page later when the receding tide replaces the swimming hole with a pebble pocked beach. The two boys, dry from their morning swims, gaze directly at the viewer with curious smiles, eager to receive someone in the flesh, their friendly wave both a hello and a goodbye. They know this moment within the reader’s gaze, like low tide, will not last. Artifacts of time even emerge like ghosts through washes of paint. The pencil drawing of a never painted pail lurks in the lower corner in a stretch of sand at high tide, its meek presence overlooked by a nearby sailboat-toting youngster. Perhaps tight deadlines or shifting compositional needs encouraged McClosky to cast aside such details, like jetsam from a burdened ship. The skeletal bucket, created with a cursory sketch, can hold, like the book itself, not a single drop of time—a reminder that this is only a drawing. In Penobscot Bay impermanence prevails—tides ebb, storms roll in and out, and children grow up, but in the pages of Time of Wonder, stasis persists.

The pages of a picture book are a fitting metaphor for life. There is an auspicious beginning, a middle full of wonder and tumult, and a shimmering, bittersweet end. When the cover closes on the final page, the characters lose their collective consciousness and enter a state of deep hibernation. For a child, a summer passes in much the same way—a full life in miniature. But unlike the child who moves on to autumnal adventures, the pages of Time of Wonder remain. Books long for readers to rouse them up from their sleep and breathe life into their pages. Like many classic picture books, Time of Wonder has been awoken by several generations since its publication in 1957, but a startling pattern has emerged—each generation seems to have significantly less of the coveted commodity of time that its pictures yearn for. Modern children engage in the unstructured natural play so beloved by the two young girls in the book with a startling lack of frequency. Instead of wandering through outdoor spaces with an observant and creative eye, children are quickly ushered through a life full of digital distractions and bloated calendars. According to Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods, the barriers to outdoor engagement are multifaceted, but the consequence is clear—children are losing their ability to observe the world around them. Time of Wonder may feel long and slow to a child not steeped in the art of marveling in the beautiful minutia of the world, but that’s what makes McCloskey’s midcentury work so prescient. As much as the pictures long for the reader’s time, today’s reader, more than ever, needs Time of Wonder to teach them the lost art of spending time watching the summer go by.